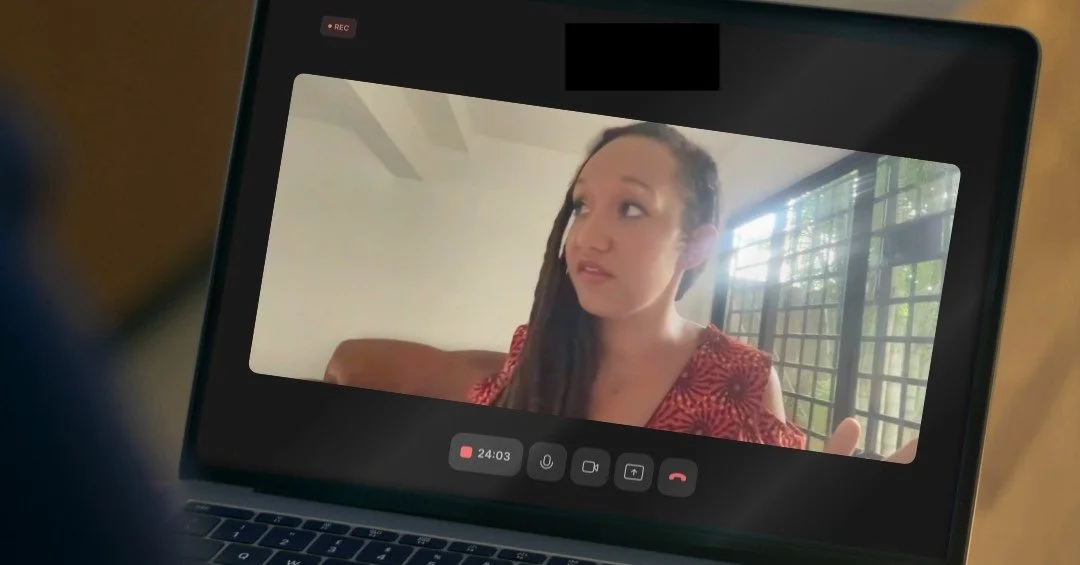

Reasoning as Relation: Opening Saltwater Reasonings with Yentyl Williams

“The body is evidence.”

We were speaking about epistemic trust: the ways Caribbean people are often taught to doubt their own knowledge, histories, and bodily knowing. Her words named a refusal of that doubt. The body carries memory. The body holds witness.

This is where Saltwater Reasonings begins.

In Season 1, across twenty-five conversations, I sit with scholars, artists, practitioners, and thinkers to explore how we make meaning, sustain intellectual life, and remain accountable to the communities and histories that shape us. All twenty-five episodes are with women. This was not my initial plan, but it is undoubtedly how the project needed to unfold. There is more to say about that, and I will return to it in a future post!

The opening conversation with Yentyl Williams sets the tone for everything that follows.

Recognition and Shared Ground

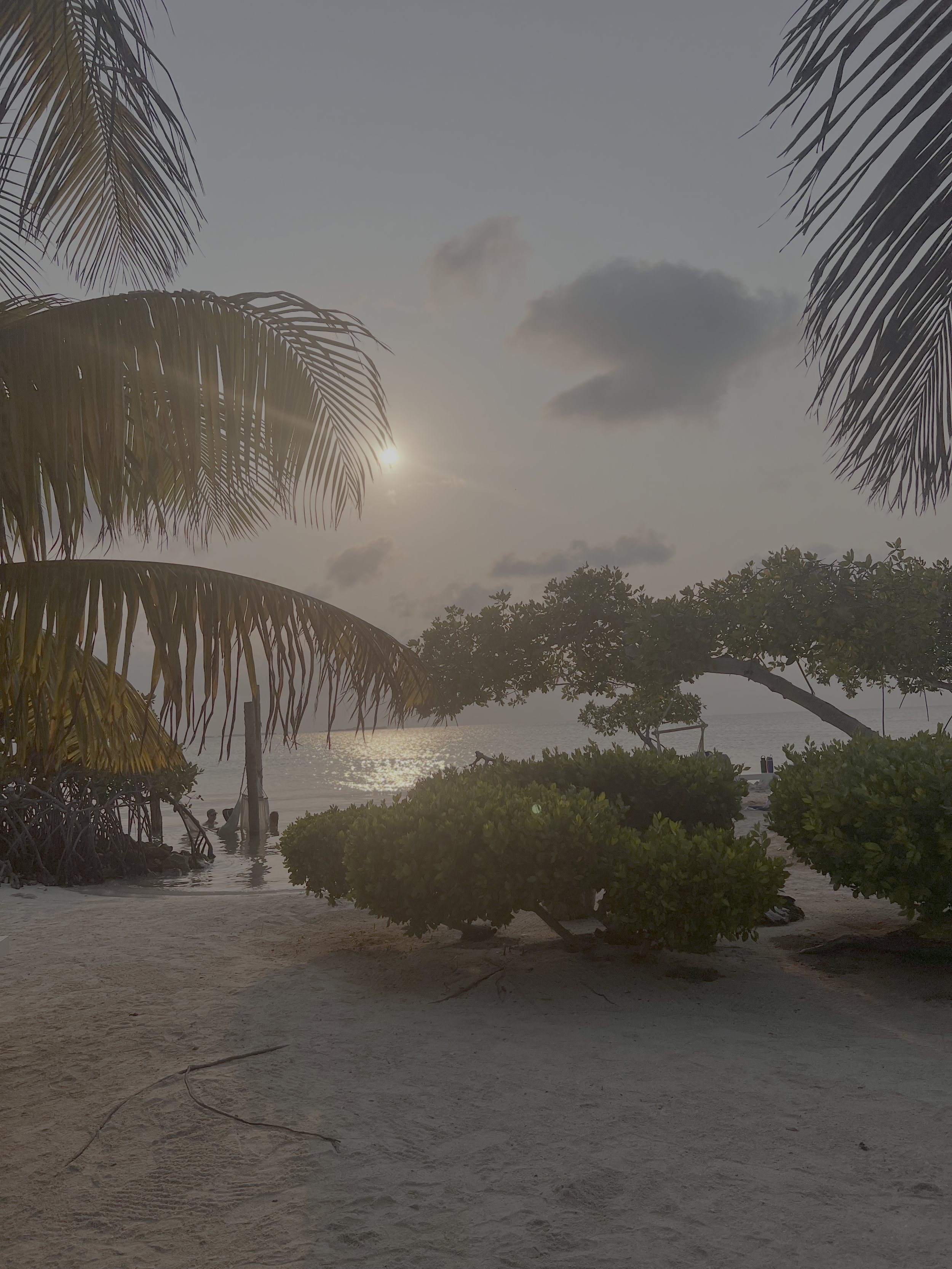

Yentyl and I met again in May 2024 in Belize, at the Caribbean Research Methodologies Conference, a regional gathering where Caribbean scholars and practitioners were in conversation about pedagogy and social justice. I remember the ease of that exchange: how quickly we found shared reference points, similar sensibilities, and a rhythm of speaking that felt familiar. It was the kind of recognition that emerges from overlapping cultural groundings and shared questions.

On a beach in Caye Caulker, Belize, we quite accidentally stumbled upon another connection. Yentyl’s mother is Edith La Chapelle. Edith, along with her sister Carol La Chapelle, was one of my dance teachers when I was a child. These women were my first encounters with the Arts. They shaped early moments of movement, creativity, and belonging that continue to live in my body and in my work.

That history mattered when we sat down to record our reasoning together. The conversation did not begin from distance. It began from relation.

Grounding in Heritage and Practice

Early in the episode, Yentyl spoke about her upbringing in Trinidad and Tobago and the influence of Rastafari philosophy on her sense of justice, responsibility, and care. She described how her parents modelled values that continue to inform her work: accountability to community, refusal of exploitation, and a commitment to keeping intellectual labour connected to lived life.

This grounding is methodological.

Yentyl’s research centres on intellectual property protection for Caribbean products and draws on Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL). TWAIL offers a framework for interrogating the colonial logics embedded in global legal systems and for imagining legal arrangements that serve emancipatory ends. In Yentyl’s hands, this work remains rooted in Caribbean realities. Her scholarship asks who benefits when Caribbean cultural and agricultural products circulate globally, and whose knowledge and labour are protected in the process.

Reasoning, in this sense, becomes both critique and reconstruction. It insists on contextual analysis grounded in place, history, and responsibility.

The Body as Evidence

The conversation returned repeatedly to embodied knowledge. Yentyl reflected on how Caribbean people are often socialised to distrust what they know, to defer to external authorities, and to treat lived experience as insufficient evidence.

“The body is evidence,” she said again, more slowly.

She meant this quite literally. The body remembers colonial violence. The body carries intergenerational knowledge. The body responds to harm, care, and presence. Reclaiming epistemic trust involves allowing bodily knowing to inform scholarly practice, rather than positioning it at the edges.

This insistence resonates deeply with Caribbean feminist and decolonial traditions. Thinkers such as Audre Lorde and Sylvia Wynter have long challenged Western epistemologies that separate mind from body and assign reason to particular kinds of bodies. Yentyl’s articulation refuses that split. Reasoning, she suggests, must include what is felt, remembered, and carried.

Intellectual Kinship and Collective Work

Toward the end of the conversation, Yentyl spoke with generosity about the Caribbean scholars who shaped her thinking and supported her intellectual journey. She named them directly, making visible the networks of care, critique, and collaboration that sustain her work.

Research, in this framing, is collective. Ideas are shaped through conversation, refined in relation, and held accountable to community rather than claimed as individual possession.

Saltwater Reasonings emerges from this same understanding. It is a space for collective reasoning, where lineages are honoured and intellectual kinship is made visible.

What Follows

This opening conversation establishes what the series will continue to explore: reasoning as a Caribbean practice grounded in relation, embodiment, and accountability. Over the next twenty-four episodes, other voices will enter this space. Some will speak about pedagogy, others about art, activism, care work, survival, refusal, or joy. All will engage reasoning as a way of being in intellectual life that honours where we come from and who we serve.

Yentyl’s voice opens the door.

The conversation continues.

Two daughters of Trinidad and Tobago, one beautiful day in Caye Caulker, Belize